Among the files on the Mossad – Israel’s Secret Intelligence Service – held at the UK National Archives are dozens of diplomatic reports and memos from the international debate which took place behind closed doors after the Israelis went into Argentina, kidnapped Adolf Eichmann, and brought him back for trial.

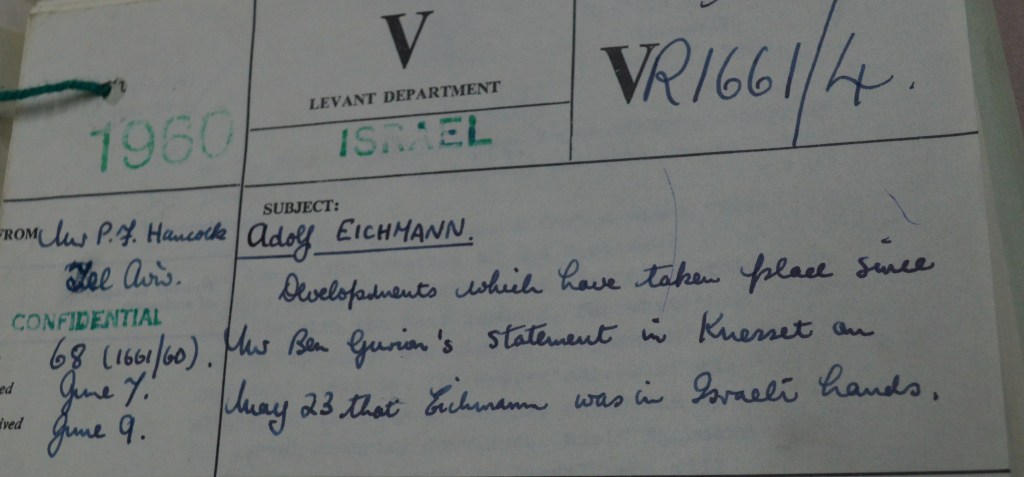

I went through these documents earlier this year when asked to research the Mossad. There were about 600 pages in all. Messages from British ambassadors in Tel Aviv and New York; Foreign Office assessments; even legal discussions about the possibility of resuming the Nuremberg trials.

I was reminded of them by Trump’s ‘snatch’ of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, and thought I’d sketch out a little of what I found.

Before I start, let me say I am certainly not saying that Maduro is Eichmann or that Trump is the Israelis. Eichmann was one of the key architects of the Holocaust. The Israelis were seeking justice for the murders of millions of Jews. There is no comparison on that level.

But I think that how the international community tried to both condemn the ‘kidnapping’ and hope the whole debate about its legality would quickly go away, is instructive.

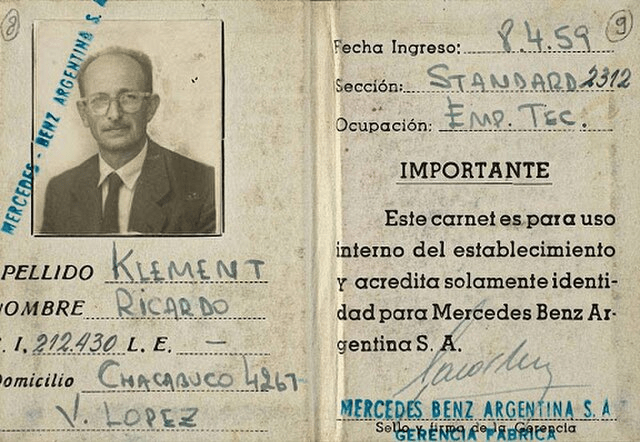

You probably know a bit about the Mossad operation which snatched Eichmann off the streets of Buenos Aires (where he had been living under the name Ricardo Clement) and flew him secretly back to Israel. What’s not so well known is the response from the international community.

Today, the capture of Eichmann is largely looked back on as an amazing piece of espionage and commando work. But that wasn’t the case at the time.

Firstly, it’s important to note that the capture of Eichmann caused shock everywhere, even in Israel, when it was announced to the Knesset by the prime minister David Ben-Gurion on May 23rd, 1960. At that point, he didn’t say where Eichmann had been captured, only that he was already under arrest in Israel and would be placed on trial. The British ambassador in Tel Aviv, Selwyn Lloyd, said the announcement was greeted by stunned silence, “followed immediately by excitement, first in the Knesset and then throughout Israel”.

In a classified report to the British government, Lloyd stated: “From the tumult, two principal questions emerge: what story lies behind Eichmann’s arrest and arrival in Israel? and what is to be done with him now?”

In fact, a debate quickly raged as to where Eichmann should be tried. The World Zionist Organization said there should be a special court presided over by Israel, but including judges from all the countries which the Nazis had occupied. But that suggestion was angrily shut down by Ben-Gurion who said the trial had to take place before an Israeli court.

But, for diplomats, the priority was the growing anger of the government in Buenos Aires, which demanded a “full explanation of how Eichmann was kidnapped and removed from Argentina”.

At first, the Israelis claimed that Eichmann had surrendered voluntarily to Jewish “volunteers” and that the Israeli government knew nothing “of the matter in advance”.

That explanation did not hold water, and, on June 8, the Argentine government requested Eichmann was returned as its nation’s sovereignty and law had been violated. It called on the Security Council of the United Nations to get involved.

This was not desirable to the western nations. A British diplomat suggested that Argentina and Israel should settle the dispute through diplomatic channels and noted that “as the Argentine government could hardly argue at this stage that the Eichmann case endangers world peace, it will be difficult for the Security Council to take any action on the matter.”

But the British secretly considered whether the Nuremberg trials of more than ten years earlier should be revived. In fact, they could not find evidence that the international tribunal at which Nazi war criminals had been tried had ever been formally dissolved; it appeared the tribunal had been “merely adjourned” and “it seems that theoretically the tribunal still has legal existence”.

On June 16th, 1960, a Foreign Office official noted: “If I am right in my view that the agreement is still in force, it may be said that the signatories [the UK, USA, USSR, and France] are under an obligation to try to arrange for Eichmann to be brought before the tribunal. This, I think, would involve trying to persuade both Israel and Argentina to agree to his surrender into the custody of one of the four powers, so as to enable him to be brought before the tribunal.”

He concluded: “I am not suggesting that this should be done, but only calling attention to the fact that this point might be raised.”

Britain’s ambassador to the United Nations, Sir Pierson Dixon, was having secret meetings with the Israelis and the Argentinians. On June 15, the Argentinian permanent representative at the UN, Dr. Amadeo, told him he had met with Israeli foreign minister Golda Meir and she had insisted that Eichmann could not be released from Israel or tried by any other than an Israeli court. Dixon noted: “She admitted that Argentine sovereignty had been violated, but the best reparation which she could offer was a letter from the Israeli government to the president of the Security Council expressing deep regret.”

Dr Amadeo declined to accept this offer on the grounds that the violation of sovereignty could only be repaired by handing back Eichmann to the Argentines, after which the nature of his trial could be determined. The Argentinian told Dixon that he had no choice now but to ask for a meeting of the Security Council.

Dixon noted that he expected most members of the council to accede to the Argentine request for a meeting and a debate and “to sympathize with the Argentine case if it is moderately presented”.

A report by Foreign Office officials in New York to the embassies in Buenos Aires, Tel Aviv, Paris, and Washington stated: “In general, we deplore any violation of sovereignty, [but], of course, there are other issues in this particular case”.

It added that any debate at the United Nations would be “coloured by the attitude of members to Israel and would be used by the Arab states as an anti-Israel issue. The less we are involved in the dispute, the better.”

The report noted that Ben-Gurion had told Le Monde that the Argentine government had no justification in going to the Security Council as “Eichmann had signed a declaration affirming that he had gone to Israel of his own free will”. A British official wrote the words “Surely dubious!” next to the typed section of this report.

Ben-Gurion added that Eichmann was not an Argentine citizen, and if the Argentine government wanted him back, “they should explain how they had come to give him shelter when they had solemnly committed themselves in 1944 to not give asylum to Nazis and war criminals”. He said that only Germany “had the theoretical right to ask for his extradition and she had not done so”.

The Security Council debated the capture of Eichmann on June 23, 1960.

Sir Pierson Dixon’s statement for the UK broadly summed up the international approach: “The kidnapping by nationals of one state of a person or persons within the territory of another state is clearly an illegal act, and one of which the international community must disapprove. On the other hand, we have the principle to which the government of Israel understandably attaches great importance. And this is the principle…that those who are accused of terrible, almost inconceivable crimes against vast numbers of innocent people should, by some means, be brought to trial. It would be wrong for this council to underestimate the strength of field on this matter among Jewish people everywhere.”

The Security Council hoped that the government of Argentina had seen that the debate had considered their feelings and hoped this would be “a symbol of the recovered harmony between the two countries”. It felt the apologies already expressed by the Israeli government “should constitute adequate reparation”.

Discussions about any further reparations were to be held between Israel and Argentina, and, on August 3, it was reported that the dispute had been settled.

A Foreign Office report noted that “good sense has indeed prevailed”.

It stated that Israel and Argentine had put out a joint communique in which “the Israelis admitted the abduction of Eichmann infringed the fundamental rights of the state of Argentina. In return, Argentina had dropped the patently unacceptable demand for Eichmann’s return.”

The stage was now clear, the diplomats noted, for the trial.

Eichmann was eventually convicted of 15 counts of crimes against humanity and was hanged in the early hours of June 1, 1962.

His last words, according to David Cesaranbi’s books Eichmann: His life and Crimes, were: “I die believing in God”.

Leave a comment